GCUK Patient Meetings - 2010 London Reports

A Gastro-Intestinal Stromal Tumour is rare, but you are not alone!

GIST Cancer UK Meeting, 22nd October 2010 At The Holiday Inn, London

Over 80 patients carers and interested professionals attended this event. The main presentation was by Dr Michelle Scurr, consultant oncologist at the Royal Marsden hospital. The planned presentation and workshop on the work of the Clinical Nurse Specialist had to be curtailed to just the workshop, because of a staff shortage at the Marsden. The meeting ended with a report from the Chair of GCUK.

Speakers

- Dr Michelle Scurr - Getting best supportive care

- Judith Robinson - Workshop on the role of the Clinical Nurse Specialist

Session Reports

Go to:

- Getting Best Supportive care (Dr Michelle Scurr)

- The work of the CNS (Workshop led by Judith Robinson)

- Chair's Report

Getting The Best Supportive Care

Talk by: Dr Michelle Scurr, Consultant Oncologist, The Royal Marsden

Michelle began by saying that this is what everyone present was doing by getting involved, finding out about their illness and learning about the best treatments available. Every GIST is different and every patient is different, so although there is a general pattern for the treatment pathways available to GIST patients, the actual care we get should be tailored for our individual needs.

To get best care, we need an informed patient, an expert oncologist and MDT, and a good NHS!

Michelle continued by giving a brief overview of GIST. (Click on each slide to see an enlarged version.)

The best estimate of the number of new cases diagnosed in the UK each year is about 800, but we do not really know. Because it is rare, it is often not diagnosed easily. GISTs may be quite big without giving any symptoms, and this does not help the diagnosis either.

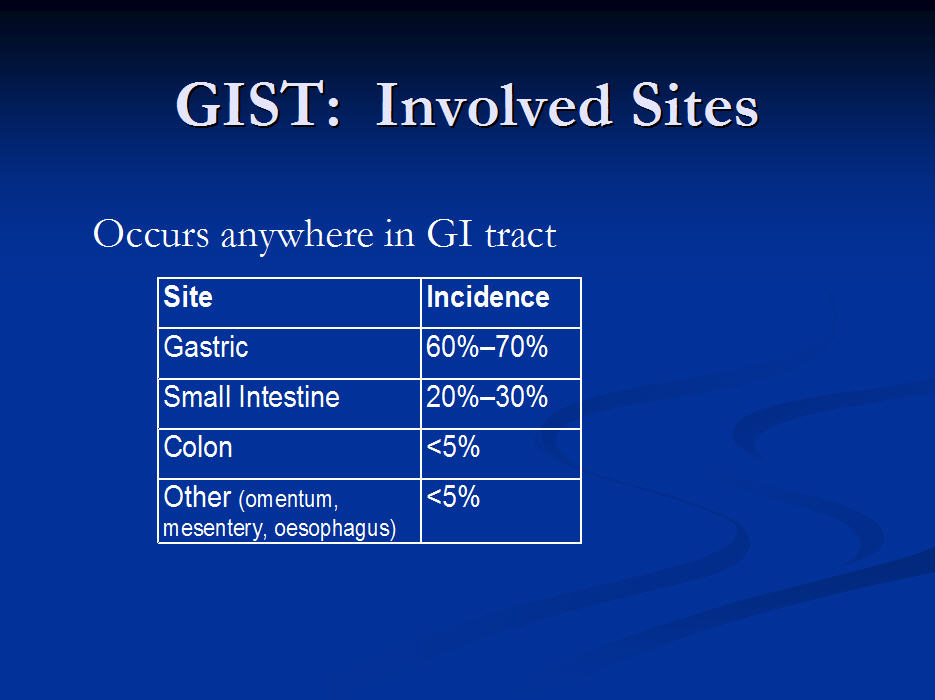

The next slide shows the frequency of occurrence of GISTs in different parts of the GI tract

These next two slides show a stained pathology sample of a GIST tumour and the molecular mechanism by which the disease spreads.

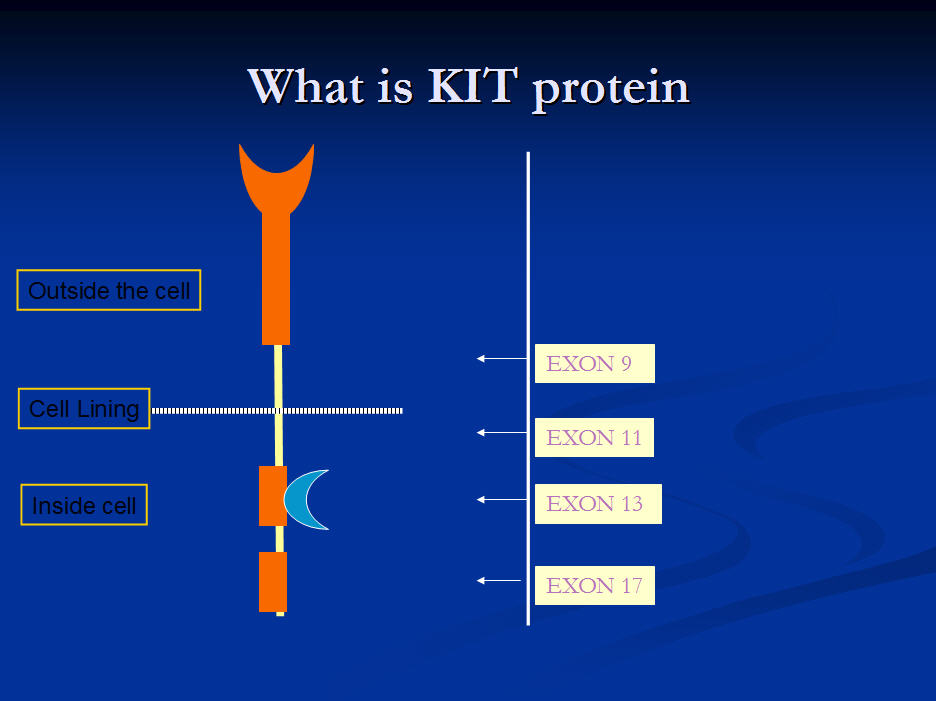

Genetic mutations of the KIT protein gene occurring in GIST.

This slide shows the relative frequency of the different GIST exons. It shows that a mutation on the Kit gene at exon 11 is by far the commonest cause of GIST

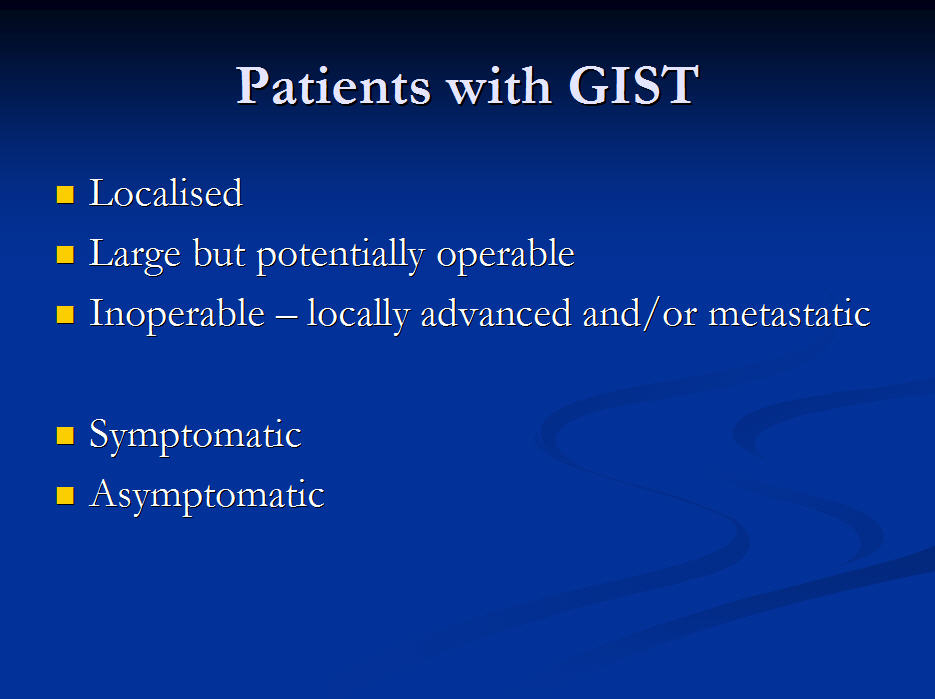

When GISTs are found they may be grouped in two ways: whether they give the patient any symptoms, and how easily they can be treated. Small GISTs can almost always be removed with surgery. Larger GISTs can probably be removed, but the surgeon may decide to try to shrink them first to make life easier for him and his patient. GISTs which have already spread, or have become very large will be treated with imatinib. This can sometimes enable the surgeon to remove them later.

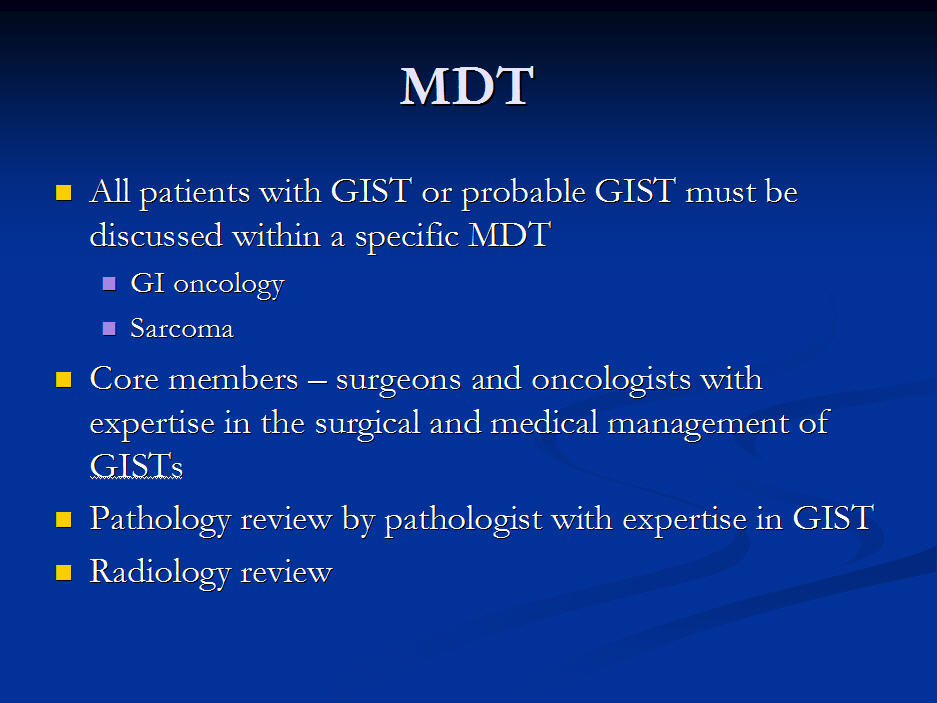

High risk tumours should be under a Multi-Disciplinary Team!

The simple removal of a small GIST, being followed up by the surgeon or the medical oncologist alone is probably fine. However if the GIST was large, high risk, or metastatic, then the patient should be in the care of an MDT (Multidisciplinary Team). This may mean referral to a major sarcoma centre where such an MDT operates. Often of course GISTs are removed as an emergency because of a bleed, or are discovered accidentally when you are having surgery for something else.

Operable Disease

Explanations of Terms used:

- Post Operative Morbidity - possible after-effects of surgery, eg eating problems after loss of all or part of stomach

- Neo-Adjuvant - using a drug (usually Glivec) to shrink a tumour to make surgery easier and less invasive.

- Adjuvant - using a drug (usually Glivec to start with) after surgery to reduce the risk of recurrence. (Currently this is only approved by NICE if the tumour has already spread, or has ruptured during surgery, when it is considered to be metastatic.)

Pre-operative Investigations

Explanations:

- EUS =Endoscopic Ultrasound

- FBC=Full Blood Count

- LFT=Liver Function test

- UEC= Urea, Electrolytes, Creatinine (showing kidney function)

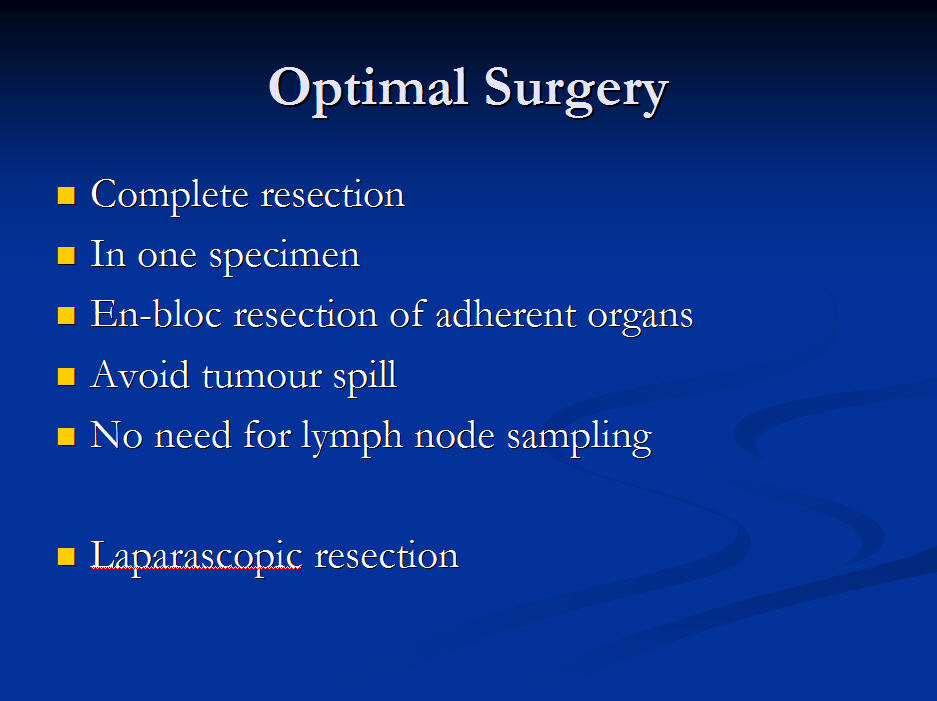

Optimal Surgery

What this means is that to get the best outcome, the GIST should be removed in one piece, and cut back to healthy tissue. Any organs attached to it should have enough removed so that the GIST is not cut in any way. Because GISTs do not spread into the lymph nodes, unlike many other cancers, these do not need to be removed.

Small GISTs in convenient places may sometimes be removed laparoscopically. This means that the patient does not have a large incision, and will recover much more quickly.

Risk of Recurrence

This table shows that the risk of recurrence depends on three factors:

- The size of the tumour (anything greater than 5cms is high risk),

- The mitotic rate: anything greater than 5/50HPF is high risk. (The mitotic rate is an indication of how fast the GIST is growing.)

- The position of the primary tumour.

White areas are very low risk, blue are low, yellow are intermediate, purple are high.

So if you have to have a GIST, you want it to be on the stomach, growing slowly, and less than 5 cms wide.

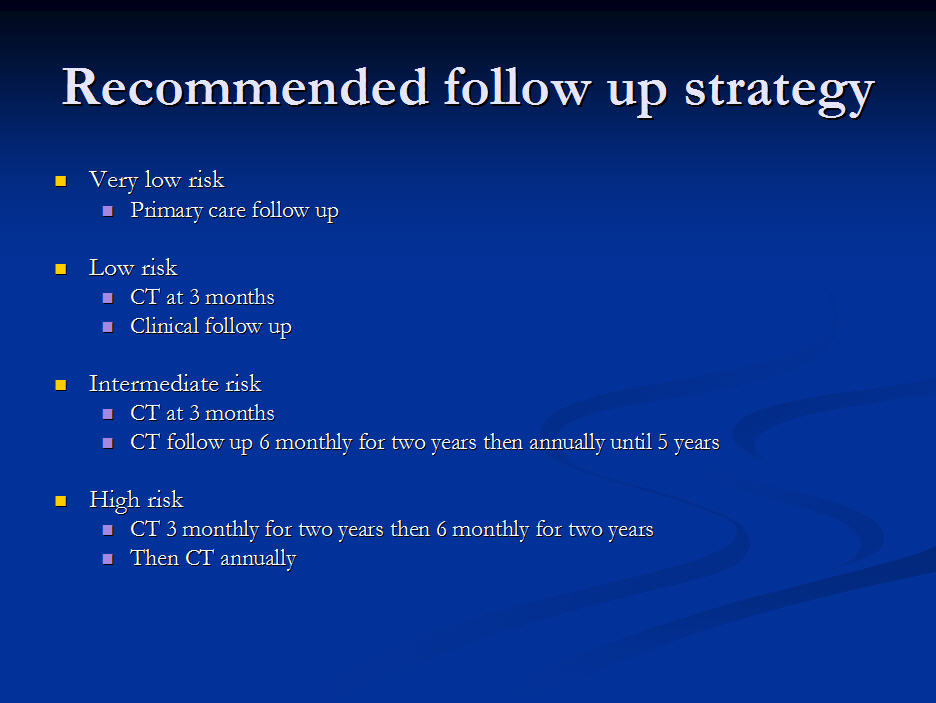

Follow Up After Surgery

There are three trials currently exploring the use of imatinib after surgery to find our whether this adjuvant treatment increases survival.

These trials are all slightly different:

- Based in US

- original tumour >3cms

- imatinib for 1 year compared with normal follow-up

- end-point is relapse

- European-based (EORTC)

- intermediate or high risk patients

- imatinib for two years compared with normal follow-up

- end-point is imatinib failure either during the trial or later (this gives an indication of overall survival)

- Scandinavian Study

- High risk

- imatinib for 1 year compared with imatinib for 2 years (end-point is overall survival)

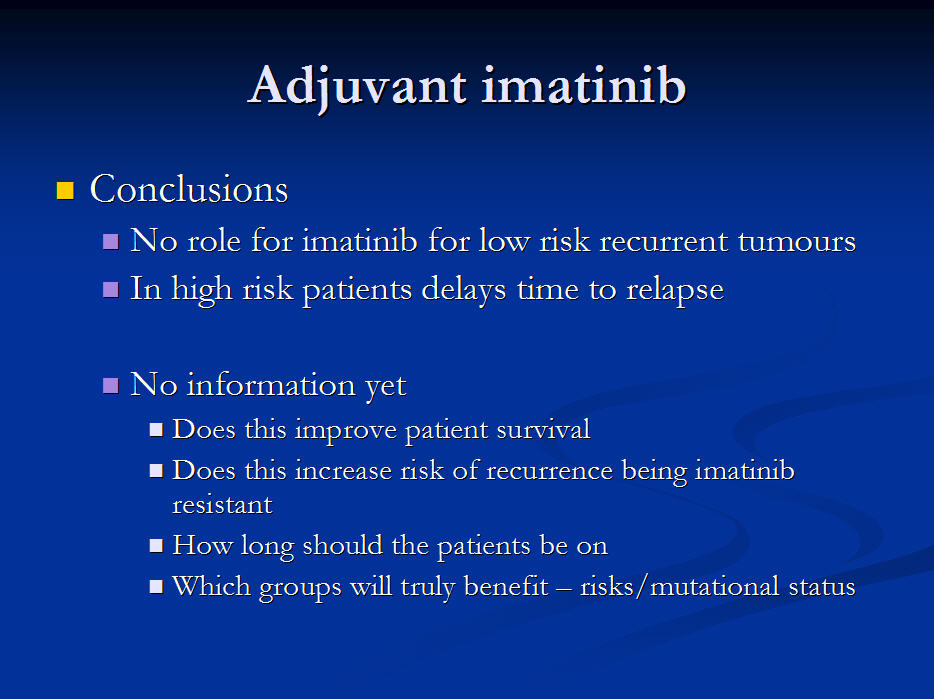

Adjuvant Treatment

Data from the first trial of adjuvant treatment (2007), which was stopped early, shows:

- There is no role for imatinib after surgery in low risk patients

- In high risk patients, imatinib delays recurrence

However, we have no evidence yet about:

- Whether taking imatinib after surgery in high-risk patients actually increases survival time

- When there is a recurrence, whether the tumour is more likely to be resistant to imatinib

- How long a high-risk patient should continue taking the imatinib

- Whether patients with some GIST mutations need adjuvant treatment more than others.

There is also a much-needed large study (UK-Europe based), with data covering 5 years. At present the data is not yet good enough on the effectiveness of Adjuvant imatinib on survival rates, but there is a probable benefit for High Risk patients in delaying recurrence.

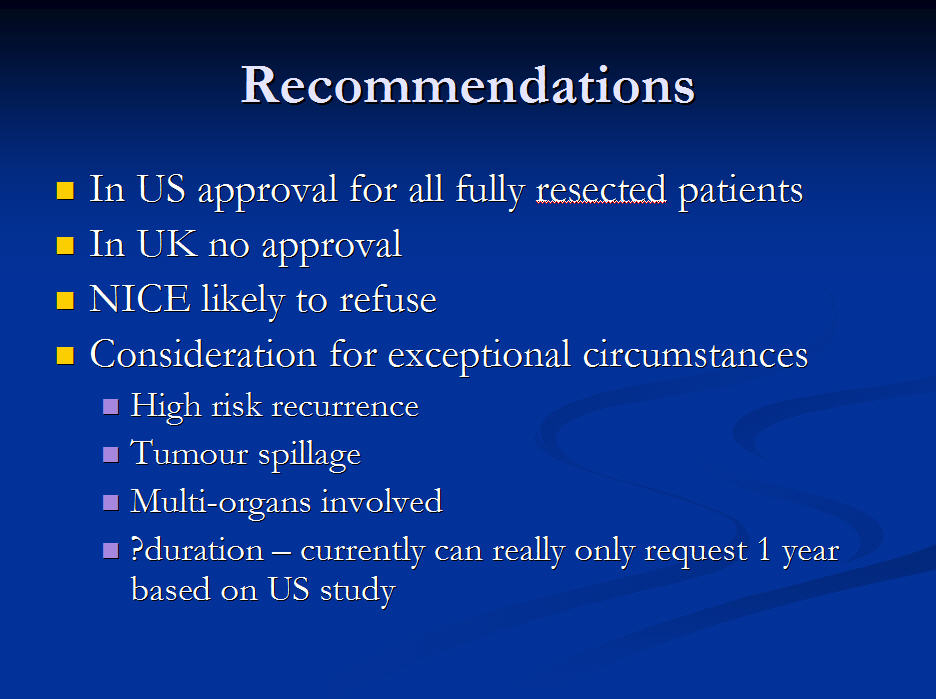

Current UK position:

Although the US and most European countries have approved the adjuvant use of imatinib for high risk patients, this is not currently approved by NICE for the UK.

However,

- if the patient is at very high risk of recurrence,

- or the GIST ruptured before or during surgery,

- or many organs were involved with the GIST,

then the oncologist can ask for these special circumstances to be take into consideration with the Primary Care Trust, who may then fund the drug for a year.

We now know that the way in which a GIST responds to imatinib depends to some degree on the mutation of the GIST. This chart shows the average response for the whole group of 127 patients, compared with the three main mutation groups, exon 11, exon 9 and wildtype, (with no known mutation.) The three colours represent, PR or Partial Response, (some tumour shrinkage), SD is stable disease, and PD/NE is progressive disease or no evidence of response.

400 vs 800mg Imatinib

There is no evidence that the choice makes a difference to survival rates. 800mg does, however, often work better for patients with an Exon 9 mutation.

Mutation Status

This information is not necessary for all new patients. It is possible to obtain the mutation status quite quickly if and when imatinib does not work.

Sunitinib

Sunitinib is now approved by NICE for patients who have progressed on 400mgs of imatinib, Because it has more than one target as a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, and because it helps to prevent the development of blood vessels to the GIST, it often works when imatinib has stopped working. However, because it affects more kinds of cells it tends to have more side-effects. It offers striking survival advantages. Exon 9 (and Wild Type) seem especially responsive, but at present the data is thin.

Michelle then summarised her suggestions as to what we should do if 400mg imatinib stops working:

- Consider mutational analysis to see whether you have Exon 11 or not

- If you are found to have a Wild-type or Exon 17 or Exon 9 mutation,, then consider applying for 800mg imatinib

- Otherwise consider moving to sunitinib.

Looking to the future

Before 2000, survival rates for metastatic disease were less than 1 year. In 2010, they are now 5-10 years.

There are many studies now being undertaken. Some are looking at new drugs, including nilotinib, being given to patients for whom sunitinib has stopped working. Some are looking at different ways of using nilotinib and sunitinib. There are also investigations into the use of Radio Frequency Ablation and surgery for metastatic disease. There is even the possibility of using Cyberknife technology.

In all cases where sunitinib has failed, it is essential to be in the care of a specialist MDT which will have access to trials and be best able to advise on the next stage. Unfortunately, as yet there is no formal listing of such MDTs.

In answer to a question Michelle Scurr said that we do not know whether secondary mutations occur spontaneously during treatment with imatinib, or become predominant when the imatinib-sensitive cells have stopped growing, having been there all the time. We do know that in metastatic disease there may be different mutations present in different tumours.

Role of the CNS in Getting Best Care

Workshop led by Judith Robinson

Because of the unavoidable absence of the CNS we had hoped to have at the meeting, Judith summarised how she saw the Clinical Nurse Specialist, Sarcoma Nurse Specialist, or whatever s/he is called in your hospital, and the very important role they can have. Ideally, they understand your needs and those of your family or carer. They understand the different possible treatment pathways, the side effects of the drugs you may be taking, and if you have difficulties of any kind, they know who to contact if they cannot solve your problem themselves.

After some discussions in small groups, it became clear that:

- Not all patients or carers knew anything about a CNS

- They had different names in different hospitals

- It was not always easy to contact them

- Some of them were extremely useful to us patients/carers

We decided that:

- When we next go to our hospitals, we should ask about a nurse specialist, and what they are called, if we do not already know about one

- We should make sure we know how to contact them

- We should encourage all hospitals to follow the best practise of giving us a card with the name or names of these people, how to contact them and when they are available

- This card should also tell us who to contact outside these hours, if we have an urgent problem.

GCUK Chair's Report - October 2010

Probably the most important development this last six months has been the beginnings of the initiative to improve the care and support of young GIST patients and their families. After our last meeting, Leigh Hibberdine and Jayne Brassington got together and the ball has started rolling. The other family involved are the McAullys, and Stacey produced a poster for the New Horizons GIST Conference in June which won first prize. (This conference is organised by Novartis for GIST and CML patient group representatives from all over the world.)

There is now a team of clinicians beginning to get a focus group under way. The idea is that this group will be a referral point for all Paediatric, Adolescent, Wild-type and Syndromic GIST patients in the UK. (PAWS-GIST for short.) The young people themselves have got a Facebook site running.

The Trustees were very sad to receive Terry Dickinson's resignation from their number, but are very glad to welcome Leigh and Jayne. They lower the average age considerably, and are bringing fresh energy to the team.

GCUK has been very much involved with NICE this year, and have had to accept the refusal to approve 800mgs of imatinib after the failure of 400mg. We submitted an appeal along with many other charities and the Royal College of Physicians, but this was turned down. The refusal to approve the adjuvent use of imatinib, but with the promise of a full re-appraisal when the trials report next year, was less of a shock. Both these treatments are approved in Scotland! We shall continue to represent GIST patients whenever we can.

GCUK has also submitted a paper to the Cancer Reform Strategy Government initiative.

Our web site is much used although it is beginning to need a re-vamp. In spite of this, it has been found to be very helpful and has had about 700 hits per month. We are planning to have a link to a new PGIST web site soon.

Leaflets are being sent out regularly, but if your hospital does not have any, do take some to put there. Or ask me for some later.

The Mailtalk group continues to be a very important part of the supporting role of GCUK. Many people contribute with information, suggestions, empathy and humour. The special phone line is also being used.

Financially, we are beginning to think we may have sufficient funds to consider a part-time administrator. This would be a great help to us, who all work as volunteers. We have had a number of generous donations from friends and patients, as well as the grants form Pfizer and Novartis, and we now have a Just-Giving site which makes it very easy and tax-efficient to give to us.

Finally, thanks to all who support our work: Novartis and Pfizer, Roger Wilson from Sarcoma UK, all our Trustees, and all of you who contribute by being willing to share your experiences. And last but probably the most important of all, our doctors, CNSs, pathologists, radiologists, and researchers.

Judith Robinson

Posted: 4/1/2011